John Kay

Biography: John Kay was born on 17 June 1704 (in the Julian calendar) in the Lancashire hamlet of Walmersley, just north of Bury. His yeoman farmer father, Robert, owned the "Park" estate in Walmersley, and John was born there. Robert died before John was born, leaving Park House to his eldest son. As Robert's fifth son (out of ten), John was bequeathed £40 (at age 21) and an education until the age of 14. His mother was responsible for educating him until she remarried.

Inventions

John Kay's son, Robert, stayed in Britain, and in 1760 developed the "drop-box", which enabled looms to use multiple flying shuttles simultaneously, allowing multicolour wefts.

The Wright brothers

Biography: The Wright brothers, Orville (August 19, 1871 – January 30, 1948) and Wilbur (April 16, 1867 – May 30, 1912), were two American brothers, inventors, and aviation pioneers who are credited with inventing and building the world's first successful airplane and making the first controlled, powered and sustained heavier-than-air human flight, on December 17, 1903. From 1905 to 1907, the brothers developed their flying machine into the first practical fixed-wing aircraft. Although not the first to build and fly experimental aircraft, the Wright brothers were the first to invent aircraft controls that made fixed-wing powered flight possible.

Inventions

In July 1899 Wilbur put wing warping to the test by building and flying a biplane kite with a five-foot (1.5m) wingspan. When the wings were warped, or twisted, one end of the wings produced more lift and the other end less lift. The unequal lift made the wings tilt, or bank: the end with more lift rose, while the other end dropped, causing a turn in the direction of the lower end. The warping was controlled by four cords attached to the kite, which led to two sticks held by the kite flyer, who tilted them in opposite directions to twist the wings.

The Wrights based the design of their kite and full-size gliders on work done in the 1890s by other aviation pioneers. They adopted the basic design of the Chanute-Herring biplane hang glider ("double-decker" as the Wrights called it), which flew well in the 1896 experiments near Chicago, and used aeronautical data on lift that Lilienthal had published. The Wrights designed the wings with camber, a curvature of the top surface. The brothers did not discover this principle, but took advantage of it. The better lift of a cambered surface compared to a flat one was first discussed scientifically by Sir George Cayley. Lilienthal, whose work the Wrights carefully studied, used cambered wings in his gliders, proving in flight the advantage over flat surfaces. The wooden uprights between the wings of the Wright glider were braced by wires in their own version of Chanute's modified Pratt truss, a bridge-building design he used for his biplane glider (initially built as a triplane). The Wrights mounted the horizontal elevator in front of the wings rather than behind, apparently believing this feature would help to avoid, or protect them, from a nosedive and crash like the one that killed Lilienthal. Wilbur incorrectly believed a tail was not necessary, and their first two gliders did not have one. According to some Wright biographers, Wilbur probably did all the gliding until 1902, perhaps to exercise his authority as older brother and to protect Orville from harm as he did not want to have to explain to Bishop Wright if Orville got injured.

Sir Richard Arkwright

Biography: Sir Richard Arkwright (23 December 1732 in Preston, - 3 August 1792 in Cromford) was an inventor and a leading entrepreneur during the early Industrial Revolution. Although the patents were eventually overturned, he is credited with inventing the spinning frame, which, following the transition to water power, was renamed the water frame. He also patented a rotary carding engine that transformed raw cotton into cotton lap.

Arkwright's achievement was to combine power, machinery, semi-skilled labour and the new raw material (cotton) to create mass-produced yarn. His skills of organization made him, more than anyone else, the creator of the modern factory system, especially in his mill at Cromford, Derbyshire. Later in his life Arkwright was known as 'the Father of the Industrial Revolution'.

Arkwright had previously assisted Thomas Highs, and there is strong evidence to support the claim that it was Highs, and not Arkwright, who invented the spinning frame. However, Highs was unable to patent or develop the idea for lack of finance. Highs, who was also credited with inventing a Spinning Jenny several years before James Hargreaves produced his, probably got the idea for the spinning frame from the work of Bray Wyatt and Lewis Paul in the 1730s and '40s.

Inventions

The machine used a succession of uneven rollers rotating at increasingly higher speeds to draw out the roving, before applying the twist via a bobbin-and-flyer mechanism. It could make cotton thread thin and strong enough for the warp, or long threads, of cloth.

His main contribution was not so much the inventions as the highly disciplined and profitable factory system he set up at Cromford, which was widely emulated. There were two 13-hour shifts per day including an overlap. Bells rang at 5 am and 5 pm and the gates were shut precisely at 6 am and 6 pm. Anyone who was late not only could not work that day but lost an extra day's pay.

Jethro Tull

Biography: Tull was born in Basildon, Berkshire, to Jethro Tull, Sr and his wife Dorothy, née Buckeridge or Buckridge. He was baptised there on 30 March 1674. He grew up in Bradfield, Berkshire and matriculated at St John's College, Oxford at the age of 17. He was educated for the legal profession, but appears not to have taken a degree. He became a member of Staple Inn, and was called to the bar on 11 December 1693, by the benchers of Gray's Inn.

Tull died in 1741 at Prosperous Farm at Hungerford. He is buried in the churchyard of St Bartholomew's Church, Lower Basildon, Berkshire, near his birthplace. His gravestone bears the burial date 9 March 1740 using the Old Style calendar, which is equivalent to the modern date 20 March 1740.

Inventions

Drill husbandry: Jethro Tull invented some machinery for the purpose of carrying out his system of drill husbandry, about 1733. His first invention was a drill-plough to sow wheat and turnip seed in drills, three rows at a time. There were two boxes for the seed, and these, with the coulters, were placed one set behind the other, so that two sorts of seed might be sown at the same time. A harrow to cover in the seed was attached behind.

On earth: Jethro Tull considered earth to be the sole food of plants. "Too much nitre," Tull tells us, "corrodes a plant, too much water drowns it, too much air dries the roots of it, too much heat burns it; but too much earth a plant can never have, unless it be therein wholly buried: too much earth or too fine can never possibly be given to their roots, for they never receive so much of it as to surfeit the plant." Again, he declares elsewhere, "That which nourishes and augments a plant is the true food of it. Every plant is earth, and the growth and true increase of a plant is the addition of more earth." And in his chapter on the "Pasture of Plants," Tull told his readers with great gravity that "this pasturage is the inner or internal superficies of the earth; or, which is the same thing, it is the superficies of the pores, cavities, or interstices of the divided parts of the earth, which are of two sorts, natural and artificial. The mouths or lacteals of roots take their pabulum, being fine particles of earth, from the superficies of the pores or cavities, wherein their roots are included."

Hoeing by hand: The hand hoe is an instrument too well known to need any description. The operation of hoeing is beneficial, not only as being destructive of weeds, but as loosening the surface of the soil, and rendering it more permeable to the gases and aqueous vapour of the atmosphere. Hoeing, therefore, not only protects the farmer's crops from being weakened by weeds, but it renders the soil itself more fertile, as more capable of supplying the plants with their food. Jethro Tull was the first who warmly and ably inculcated the advantages of hoeing cultivated soils. He correctly enough told the farmers of his time, that as fine hoed ground is not so long soaked by rain, so the dews never suffer it to become perfectly dry. This appears by the plants which flourish in this, whilst those in the hard ground are starved. In the driest weather good hoeing procures moisture to the roots of plants, though the ignorant and incurious fancy it lets in the drought.

James Hargreaves

Biography: James Hargreaves was born at Stanhill, Oswaldtwistle in Lancashire. He was described as "stout, broadset man of about five-foot ten, or rather more". He was illiterate and worked as a hand loom weaver during most of his life. He married and baptismal records show he has 13 children, of whom the author Baines in 1835 was aware of '6 or 7'. He was survived by eight children.

Inventions

The idea for the spinning jenny is said to have come from the inventor seeing a one-thread wheel overturned upon the floor, when both the wheel and the spindle continued to revolve. He realized that if a number of spindles were placed upright and side by side, several threads might be spun at once. The spinning jenny was confined to producing cotton weft, it was unable to produce yarn of sufficient quality for the warp. High quality warp was later supplied by Arkwright's spinning frame.

Thomas Savery

Biography: Thomas Savery (c. 1650–1715) was an English inventor and engineer, born at Shilstone, a manor house near Modbury, Devon, England. He is famous for his invention of the first commercially used steam powered engine.

Inventions

Fire Engine Act: Savery's original patent of July 1698 gave 14 years' protection; the next year, 1699, an Act of Parliament was passed which extended his protection for a further 21 years. This Act became known as the "Fire Engine Act". Savery's patent covered all engines that raised water by fire, and it thus played an important role in shaping the early development of steam machinery in the British Isles.

Application of the engine: A few Savery engines were tried in mines, an unsuccessful attempt being made to use one to clear water from a pool called Broad Waters in Wednesbury (then in Staffordshire) and nearby coal mines. This had been covered by a sudden eruption of water some years before. However the engine could not be 'brought to answer'. The quantity of steam raised was so great as 'rent the whole machine to pieces'. The engine was laid aside, and the scheme for raising water was dropped as impracticable. This may have been in about 1705.

Robert Fulton

Biography: Robert Fulton was born on a farm in Little Britain, Pennsylvania, on November 14, 1765. He had at least three sisters – Isabella, Elizabeth, and Mary, and a younger brother, Abraham. He then married Harriet Livingston and had four children, Julia, Mary, Cornelia, and Robert. His father, Robert, had been a close friend to the father of painter Benjamin West, (1738-1820). Fulton later met West in England and they became friends.

Inventions

He became caught up in the enthusiasm of the "Canal Mania" and in 1793 began developing his ideas for tub-boat canals with inclined planes instead of locks. He obtained a patent for this idea in 1794 and also began working on ideas for the steam power of boats. He published a pamphlet about canals and patented a dredging machine and several other inventions. In 1794 he moved to Manchester to gain practical knowledge of English canal engineering. Whilst there he became friendly with Robert Owen, the cotton manufacturer and early socialist. Owen agreed to finance the development and promotion of his designs for inclined planes and earth-digging machines and was instrumental in introducing him to a canal company where he was awarded a sub-contract. However, this practical experience was not a success and he gave up the contract after a short time.

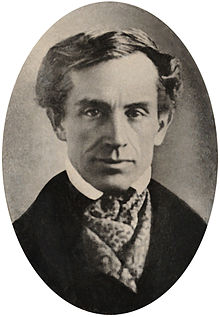

Samuel F. B. Morse

Biography: Samuel F. B. Morse was born in Charlestown, Massachusetts, the first child of the pastor Jedidiah Morse (1761–1826), who was also a geographer, and his wife Elizabeth Ann Finley Breese (1766–1828). His father was a great preacher of the Calvinist faith and supporter of the American Federalist party. He thought it helped preserve Puritan traditions (strict observance of Sabbath, among other things), and believed in the Federalist support of an alliance with Britain and a strong central government. Morse strongly believed in education within a Federalist framework, alongside the instillation of Calvinist virtues, morals and prayers for his first son.

Inventions

Telegraph: As noted, in 1825 New York City had commissioned Morse to paint a portrait of Lafayette in Washington, DC. While Morse was painting, a horse messenger delivered a letter from his father that read, "Your dear wife is convalescent". The next day he received a letter from his father detailing his wife's sudden death. Morse immediately left Washington for his home at New Haven, leaving the portrait of Lafayette unfinished. By the time he arrived, his wife had already been buried. Heartbroken that for days he was unaware of his wife's failing health and her death, he decided to explore a means of rapid long distance communication.

Relays: Morse encountered the problem of getting a telegraphic signal to carry over more than a few hundred yards of wire. His breakthrough came from the insights of Professor Leonard Gale, who taught chemistry at New York University (he was a personal friend of Joseph Henry). With Gale's help, Morse introduced extra circuits or relays at frequent intervals, and was soon able to send a message through ten miles (16 km) of wire. This was the great breakthrough he had been seeking. Morse and Gale were soon joined by Alfred Vail, an enthusiastic young man with excellent skills, insights and money.

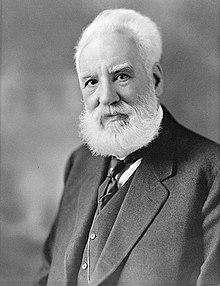

Alexander Bell

Biography: Alexander Bell was born in Edinburgh, Scotland, on March 3, 1847. The family home was at 16 South Charlotte Street, and has a stone inscription marking it as Alexander Graham Bell's birthplace. He had two brothers: Melville James Bell (1845–70) and Edward Charles Bell (1848–67), both of whom would die of tuberculosis. His father was Professor Alexander Melville Bell, a phonetician, and his mother was Eliza Grace (née Symonds). Born as just "Alexander Bell", at age 10 he made a plea to his father to have a middle name like his two brothers.[N 6] For his 11th birthday, his father acquiesced and allowed him to adopt the name "Graham", chosen out of respect for Alexander Graham, a Canadian being treated by his father who had become a family friend. To close relatives and friends he remained "Aleck".

As a child, young Bell displayed a natural curiosity about his world, resulting in gathering botanical specimens as well as experimenting even at an early age. His best friend was Ben Herdman, a neighbor whose family operated a flour mill, the scene of many forays. Young Bell asked what needed to be done at the mill. He was told wheat had to be dehusked through a laborious process and at the age of 12, Bell built a homemade device that combined rotating paddles with sets of nail brushes, creating a simple dehusking machine that was put into operation and used steadily for a number of years. In return, John Herdman gave both boys the run of a small workshop in which to "invent".

Inventions

Telephone: By 1874, Bell's initial work on the harmonic telegraph had entered a formative stage, with progress made both at his new Boston "laboratory" (a rented facility) and at his family home in Canada a big success.[N 14] While working that summer in Brantford, Bell experimented with a "phonautograph", a pen-like machine that could draw shapes of sound waves on smoked glass by tracing their vibrations. Bell thought it might be possible to generate undulating electrical currents that corresponded to sound waves. Bell also thought that multiple metal reeds tuned to different frequencies like a harp would be able to convert the undulating currents back into sound. But he had no working model to demonstrate the feasibility of these ideas.

Eli Whitney

Biography: Eli Whitney (December 8, 1765 – January 8, 1825) was an American inventor best known for inventing the cotton gin. This was one of the key inventions of the Industrial Revolution and shaped the economy of the Antebellum South. Whitney's invention made upland short cotton into a profitable crop, which strengthened the economic foundation of slavery in the United States. Despite the social and economic impact of his invention, Whitney lost many profits in legal battles over patent infringement for the cotton gin. Thereafter, he turned his attention into securing contracts with the government in the manufacture of muskets for the newly formed United States Army. He continued making arms and inventing until his death in 1825.

Inventions

Cotton gin: The cotton gin is a mechanical device that removes the seeds from cotton, a process that had previously been extremely labor-intensive. The word gin is short for engine. The cotton gin was a wooden drum stuck with hooks that pulled the cotton fibers through a mesh. The cotton seeds would not fit through the mesh and fell outside. Whitney occasionally told a story wherein he was pondering an improved method of seeding the cotton when he was inspired by observing a cat attempting to pull a chicken through a fence, and could only pull through some of the feathers.

Milling machine: Machine tool historian Joseph W. Roe credited Whitney with inventing the first milling machine circa 1818. Subsequent work by other historians (Woodbury; Smith; Muir; Battison [cited by Baida]) suggests that Whitney was among a group of contemporaries all developing milling machines at about the same time (1814 to 1818), and that the others were more important to the innovation than Whitney was. (The machine that excited Roe may not have been built until 1825, after Whitney's death.) Therefore, no one person can properly be described as the inventor of the milling machine.

No comments:

Post a Comment